Raising capital is a long-term relationship, not a transaction.

This guide offers a practical, founder-first lens on raising capital, drawn from dozens of real conversations and private insights from Insight Managing Directors, Hilary Gosher, Ryan Hinkle, Byron Lichtenstein, and Teddie Wardi, who together have over six decades of investing experience.

Let us take you through the entire capital-raising journey: From getting investor-ready and crafting your pitch, to choosing the right investor, managing the relationship, and planning your exit. We’ll focus on how to approach fundraising across early, growth, and late stages, so you understand what changes as you scale and how to build investor relationships that work for you and deliver real value for your business.

The fundraising landscape has shifted significantly since the 2020-2021 highs. Valuations have compressed, capital is more selective, and investors are digging deeper into business fundamentals. While this guide is evergreen, founders should always layer in an honest look at their timing, runway, and the current market mood when planning a raise.

Inside, you’ll find advice on:

- How to choose the right investor

- What investors are looking for — and how it evolves by stage

- What makes a great pitch

- How to use Rule of 40 as a tool for durable growth

- Creating a true partnership with your investors and board

- Planning for an exit from day one

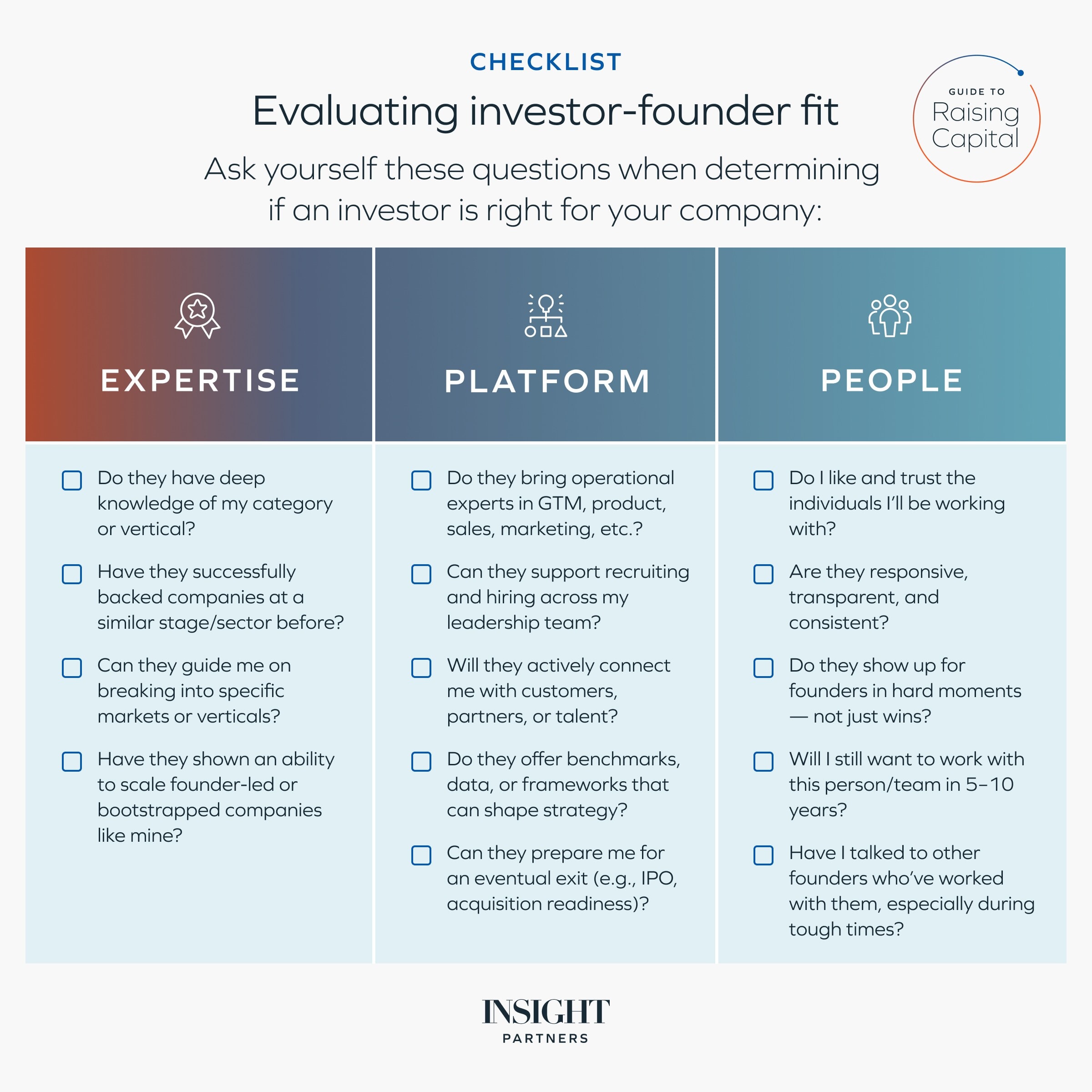

Investor-founder fit

“As investors, we always talk about product-market fit as a thing. But I think investor-founder fit is an equally important concept,” says Teddie Wardi, managing director, Insight Partners.

You need to think about what you need from your investor beyond the capital. That means evaluating not just the people you will be working with day to day, but also the institutional capabilities of the firm. “It comes down to the capability fit,” he adds. “Can the investor do the things that you want them to do, whether it’s building out the team, bringing prospects, or bringing other types of partnership opportunities.”

In short, the right fit for a founder-investor relationship comes down to three things:

- Expertise. Does the investor invest in and understand your category and vertical?

- Advisory. Can the firm deliver what you need — peer networks, market access, operational support?

- People. Who will you be working with? Do you like and trust them? Do you see yourself working with those people for the next 5-10 years?

Expertise

“The most important part of the investor-founder relationship is the idea that the investor knows the industry, knows the market, has seen the playbook before, and is able to really provide guidance to the founder,” says Hilary Gosher, managing director, Insight Partners.

That guidance should be tied to your needs: hiring, go-to-market, breaking into key accounts — whatever the key priorities are. “Founders should really think about what they want from an investor, and then select a subset of investors to talk to based on those areas of expertise,” says Wardi. “Sometimes it helps to put together a syndicate of investors. […] you don’t want people who have the same exact expertise. You want to mix and match different areas of knowledge.”

Generally, you want an investor who has experience in the target vertical of your startup, but it does depend on the context. If, for example, you’re building a product that is deep in the workflows of healthcare companies, you will want an investor that has done it before and understands the nuances of the industry. On the other hand, if you’re building something more horizontal that happens to touch a few specialized verticals — cybersecurity for manufacturing and financial services, for instance — the investor’s understanding of cyber as a whole probably matters more than the understanding of those verticals.

This is particularly important if you’ve bootstrapped your business. “Sometimes it’s about scaling beyond your own skill set,” says Wardi. “Sometimes it’s about de-risking your personal finances. Sometimes it’s about breaking into a new market or funding M&A.” Whatever the reason, you should pay special attention to what investors you work with. Will they add value without breaking what works? Have they helped other founder-controlled businesses scale before?

Advisory & Network

Look for an investor that has functional experts with real operational experience in the areas that matter most to you. At Insight Partners, we offer GTM and operational support via Insight Onsite, a dedicated team of 130 professionals that help fuel portfolio company growth. “Insight really was the very first firm to think ‘How do we support a founder with more than just capital?’ And our founder, Jeff Horing, had the vision to bring expertise in house to make sure that the founder had access to that expertise as they were scaling and growing,” says Gosher.

We see this deep, hands-on operational knowledge across nearly every corner of the software industry to be a critical part of helping founders succeed. “Because Insight invests almost exclusively in software companies, we have a very strong understanding of what it takes for a company to scale when they’re early, when they’re in their growth stage, and when they’re in their late stage,” says Gosher. “And we have functional experts in each area that allow a company to understand what best practices look at their stage of growth.” That means sales, marketing, product, R&D, customer success — all the areas that a CEO and their direct reports need to scale their business.

In addition to expertise, the investor team should offer access. That means help in sourcing, calibrating, and hiring the best talent as you scale and grow, and opening doors to buyers.

Equally powerful is the peer network an established investor can bring. “The fact that we have very experienced Series B, Series D, and late-stage CEOs who can serve as mentors to those Series A companies is a very powerful component of what we bring to the table,” says Gosher. “Not only do we bring the data of what it looks like to scale at every stage, and what your data and benchmark should look like, but […] There’s a CEO who has been through it before, who has walked a mile in your shoes, and who can provide you with guidance and expertise.”

Finally, if you’re planning to get acquired or IPO, look for an investor who can help you throughout the process. Insight Onsite has a program called “Exit Prep” that helps founders anticipate what a buyer is going to ask and have that data ready — revenue, retention rates, cohort analysis, the size of your market, cross-sell, and downsell opportunities. “Being exit ready means that you have clear data, clear financials, and a story that stands up to scrutiny,” says Gosher. “We help you prepare for the exit by understanding who your customers are, what are your financials, and how do those financials support a compelling story, and why is this sustainable?”

People

Ultimately, signing a term sheet means entering a relationship with the investor. And a long one. You’re choosing a partner for the next 5-10 years, so make sure you’re aligned with your investors on what you’re trying to achieve. “It comes down to the fit of the person you’d be working with,” says Ryan Hinkle, managing director, Insight Partners. “At Insight, the team that you work with at the beginning is the team you work with forever, and we want to create that relationship with you so that you understand exactly what motivates us to motivate you.”

You should also think about what happens when things go wrong. Talk to as many founders as possible who’ve worked with the firms you’re considering to understand how they operate, “not just in the good times, but in trickier times,” says Hinkle. “Who’s there in the trenches with you? Who’s there to help figure problems out? Who’s there in the boardroom to say, ‘We made that decision together. It didn’t work out, but we own our share of that decision.’ Who does what they say, and says what they’re going to do with 100% conviction and consistency? Those are the elements we expect in our relationships with all of the companies we work with.”

What investors really want (at every stage)

The best time to raise money is when you don’t need it.

“You want to raise capital when you have sufficient runway to execute on your plan, but would love more capital to turbocharge whatever your growth ambitions might be,” says Hinkle.

But before you do, you need to be clear on what those ambitions are. Why are you raising? What are you trying to achieve? And how will the capital, and the right investor, accelerate your journey?

Investor expectations evolve with each stage of your company’s growth. Here’s what they look for and how to meet them.

Early stage

At this stage, you’re selling potential. Investors are betting on your founding team, clarity of vision, understanding and articulation of the ideal customer profile (ICP), and market potential and timing. They’re looking for initial customer traction, momentum, and your willingness to experiment, learn, and iterate on repeat.

Strength of the founding team

Investors are always buying into the team. “We’re always betting on the people who are going to actually take that product and that business, and go tackle that problem,” says Byron Lichtenstein, managing director, Insight Partners. That means emphasizing not just the strength of your current roster, but that you have a strategy for how you will continue building out your team with the right people for the opportunity you’re going after.

Getting from zero to one

It’s not just the strength of the team investors are evaluating, but also whether the founders have a deep understanding of the market and customer problem you’re solving. Wardi discusses the best pitches from these founders, saying “They’re approaching it from understanding the customer’s pain point. Understanding not just what they need to solve, but why would they want to solve this today?” says Wardi. “They usually have very concrete steps of how to build the company out, not just the vision, but the steps to go from zero to one. Those are key ingredients in the early-stage pitch.”

Early traction

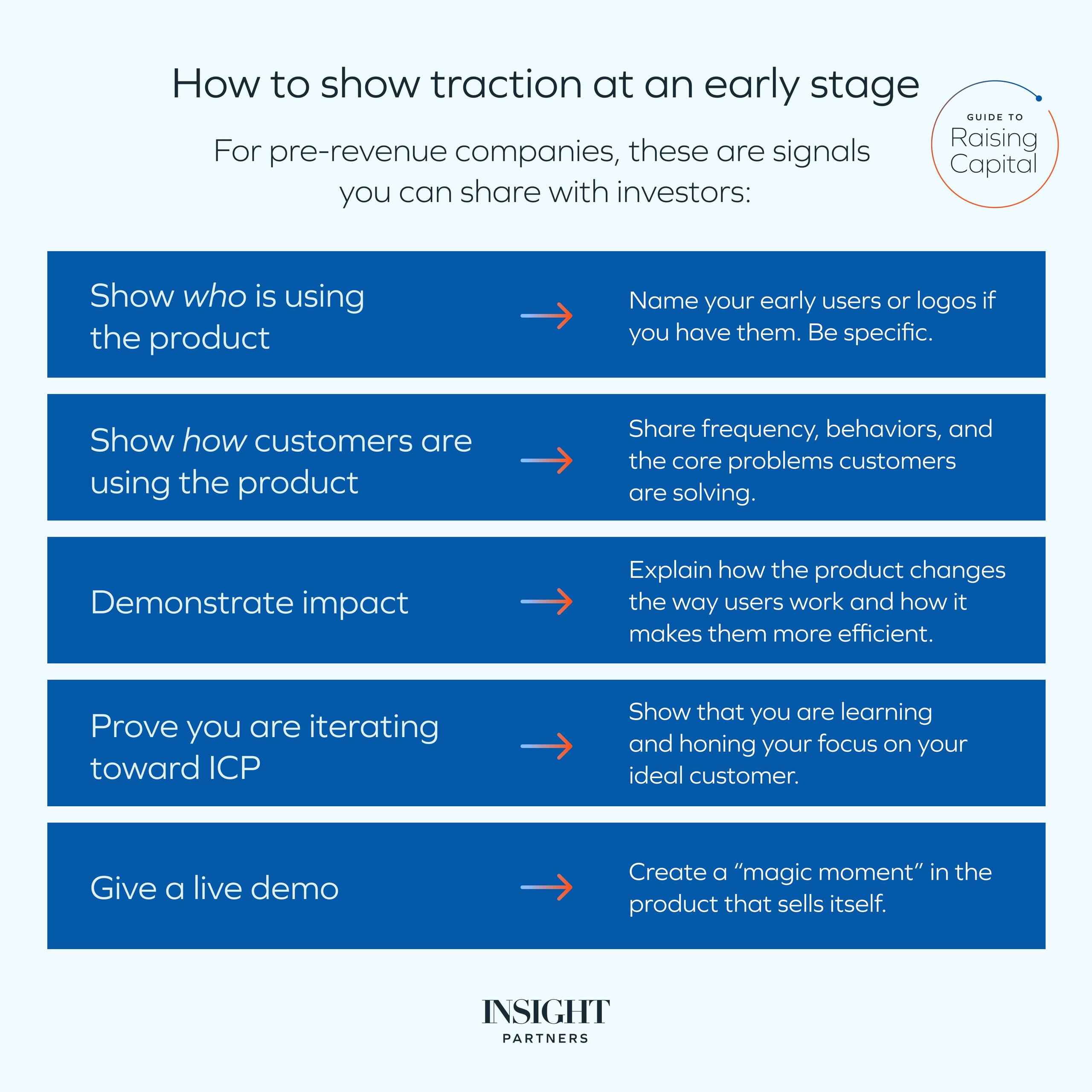

In the earliest stages, when you don’t have revenue signals or much quantitative data, you need to show traction in other ways.

The best proof is how your early users are engaging with your product. Who’s using the product, how are they using it, and how often? What problems are they solving with it? How is it changing the way they work? Investors want to know that you’re iterating towards the ideal customer profile — and that there are millions of other customers out there who would be prepared to pay money for that same product.

“Someone once told me that the best indicator for enterprise software is that it gets someone promoted,” says Wardi. “So if you can really show that you have these evangelists at the customer and how their job becomes better, maybe they get promoted or otherwise recognized, that’s usually a good predictor for a successful product.”

Give a demo

“Investors love to see the product first hand,” says Wardi. “You’re going to go out in the world and sell your product, so making good first impressions with the product, and having it sell itself and create a magic moment quickly is important.”

Growth stage

At growth, you’re proving traction and repeatability. Investors are looking for clear product-market fit, repeatable go-to-market, and solid unit economics.

The right metrics — instrument your business for success

Investors care about all the core SaaS metrics: net revenue retention, customer acquisition cost, churn, market size. But what stands out is your understanding of what’s driving those numbers, and your ability to act on them. “One of the most important things that you can do at the growth stage is instrument your business for success,” says Gosher. “Make sure that you have the data that you need at your fingertips in order to be able to make the right decisions and to course correct.”

And metrics aren’t just about what’s happened. They’re about where you’re going, telling the story of your future growth. “Connecting the current course and speed trajectory to your own articulation of your thesis is really important,” says Hinkle. “It all comes back to metrics as a vocabulary to help us keep score.”

TAM that supports the journey

TAM matters, but not as a vanity number. “We need to know that you’ll be able to sustain growth over the long term. We need to know that there’s sufficient market runway — that if you churn through some customers, there’s a lot more to go and get,” says Gosher. “In a vertical market that is constrained by TAM, if you churn through customers in early stages because you don’t fully have good product-market fit, or because you have a competitor, or you haven’t priced correctly, and you churn through customers, it may be very hard to get them back. And there may not be that many more to go after.” You need to show you have enough headroom to learn, iterate, and sustain growth over the long term.

A growth mindset

The team still matters, but now it’s about maturity and adaptability to change. “How coachable are you? How willing are you to take feedback? How willing are you to surround yourself with experts? How willing are you to bring other voices to the table so that you can learn, grow, iterate, experiment, and finally land on the vein of gold that’s going to allow you to scale efficiently and quickly?” says Gosher.

Late stage

At later stages, investors are looking for defensibility, scale efficiency, market leadership, and evidence of a second act.

Protecting the moat

At later stages, you’re going to be talking more about competition, and the risk of encroachment. “As an early company, you’re a new entrant. You’re an attacker. You’re a disruptor. As a later-stage company, you’re a defender,” says Hinkle. “You’re trying to protect and preserve the moat that you’ve built.”

Concrete results

With more time on the clock, fewer of the questions that were live at the early stage are unanswered. So investors are looking for concrete outcomes. What did you achieve in revenue? What did you achieve in EBITDA?

“An investor is really asking themselves two questions: What can go right? And what can go wrong?” says Hinkle. “The more evidence you have as to the ‘what can go right’ piece, and the more support you have to avoid what can go wrong, the easier the fundraising journey is.”

A credible second act

If you plan on going public soon, you need to be able to show that you have “a second act, or if not a second act, a current act that has lots of legs.” says Gosher. “You need to be able to sustain growth quarter after quarter for many months.” That means a large TAM, a large customer base that will continue to buy more, geographic expansion opportunities or new products you can sell back to the existing base, repeatable motions, and predictable revenue.

“What really matters is the CEO and the management team understand what it means to be a public company,” says Gosher. “They’re bought into the notion of managing quarterly earnings and quarterly guidance to the Street, and they have the internal infrastructure to be able to report, to be able to course correct, and to be able to manage their business because they’re fully instrumented in terms of getting the right data, making the right decisions, and being able to understand where future growth is going to come from.”

What makes a great pitch — at any stage

Ultimately, the fundamental questions investors ask at every stage are very similar:

- What is the problem you’re solving?

- Why is your solution unique and durable?

- What is the potential return at a given deal structure?

So frame your pitch around those questions. No matter what letter of the series you might be raising, you’re always trying to articulate your product-market fit, your unit economics, and you’re arguing why more capital can accelerate a path to a future you envision and believe you can achieve.

Be genuine

“The best pitches are authentic,” says Gosher “They’re talking about stuff that comes from the heart, that is a true passion where they truly understand why they’re supporting the customer and they have the customer’s interests at heart.” That means having the person who is the most knowledgeable do the most talking — and that might not be the founder. It might be the head of product who can really talk about the passion for the product, the problem you’re solving, and why customers are buying it.

Know your audience

The best pitches at all stages should have an audience of one. “As with any sales process, speak to the interest of the person that you’re pitching to,” says Gosher. That means doing research on the investment firm you’re pitching to. What have they invested in in the past? What kind of verticals are they interested in? And be honest about the stuff you need from that investor and why you think it would be a good partnership. “The worst pitches are the pitches where it’s a canned presentation,” she adds. “It’s not tailored to the audience, the numbers are not believable, the TAM sizes are hard to get your head around, and it feels very perfunctory.”

Understand, don’t dismiss, the competition

Instead of dismissing your rivals, show that you’ve studied them, and how you’re different.

“One of my pet peeves of pitches is that classic two by two competitor matrix where your company is at the top-right corner […] Then some other competitive company which is worth like $10 billion and still growing is at the bottom-left,” says Wardi. “It’s just very intellectually dishonest.”

Use metrics to tell your story

“If I think of the best pitches, it’s like they’re in my head,” says Hinkle. “It’s like they know all of the metrics that get me all just wired up and excited about the company. […] Look at this 98% GDR. Look at this two-month CAC payback. Look at this zero cost to renew. […] But more importantly they’re painting the picture of why this problem is endurable forever, and why they’re uniquely positioned with a good tech moat to really have a commanding chunk of that market.”

Rule of 40 is out. Rule of Insight is in.

The ‘Rule of 40’ — revenue growth plus profit margin is equal to or greater than 40% — has long been the common shorthand for SaaS performance.

And as competition for capital intensifies, particularly in bull markets or later-stage funding rounds, some investors have raised the bar to Rule of 50 or 60. ‘Rule of bigger’ has become the general view.

This works as a rule of thumb, but it comes up short when you, and investors, want to really understand how your business is doing. Not all Rule of Xs are created equally. “We would happily trade 40% durable growth and zero profit all day for zero growth, 40% profit. The first one is way more valuable,” says Hinkle.

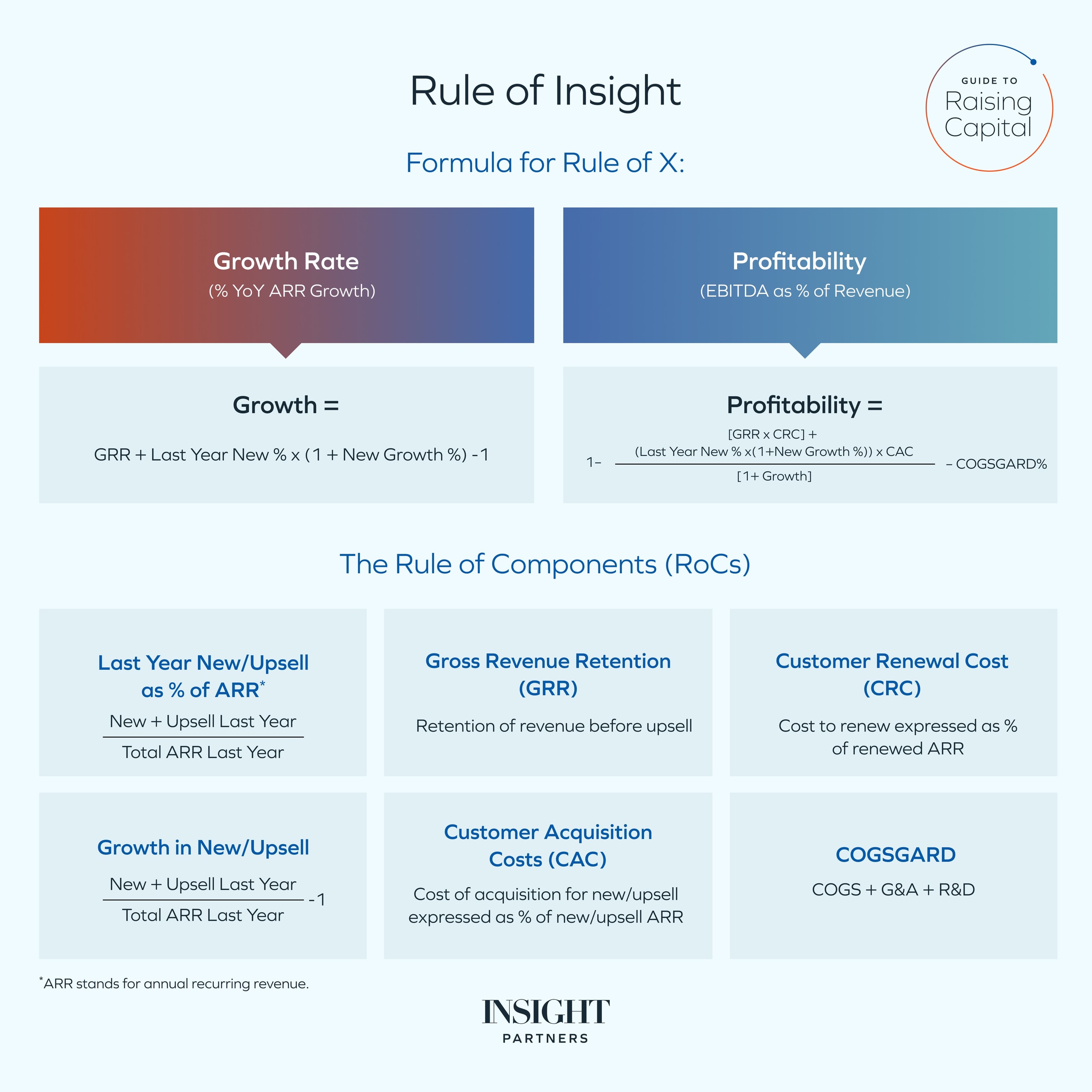

At Insight, we have developed a more nuanced framework: The Rule of Insight. It’s based on six foundational metrics — what we call ‘Rule of’ Components (RoCs) — that help you understand and manage the levers of growth.

“The whole philosophy of Rule of Insight is to have an appreciation that one and only one indicator to describe the health of a business is just too limited,” says Hinkle. “What I push really hard when I’m in boardrooms is to understand that there are six different variables that if you capture those, you can derive ‘Rule of’, and even more importantly, you can derive what ‘Rule of’ would be at various growth rates.”

The Rule of Insight and the six RoCs

Together, these six RoCs offer a more holistic view of growth, profitability, and long-term value:

1) New revenue / total revenue (Ratio)

The proportion of revenue from new customers vs total revenue. This is a key indicator of whether your growth is coming from new customers or your existing base.

2) Growth rate of new business

How quickly new customer revenue is growing, excluding revenue from existing customers. This is a forecasted variable, helping to project your total growth potential.

3) Customer acquisition cost (CAC)

Spend on sales and marketing per $1 of new revenue. This helps determine how scalable your go-to-market motion is.

4) Customer retention cost

The cost to retain existing customers. This is a less commonly measured but vital metric that measures how efficient your renewal motion is. A low customer renewal cost can help drive more profitability in the future.

“I know how much Netflix spends to retain me. […] They send a ping to my credit card, I pay the bill, and it’s over — basically a zero customer renewal cost,” says Hinkle. “There are other businesses where they have to re-prove their value to me every single time a renewal comes around.”

5) Gross revenue retention (GRR)

The percentage of last year’s revenue retained this year, excluding upsell. This affects both growth and profitability, critical to long-term stability.

6) COGS + G&A + R&D = ‘CogsGARD’

This combines non-sales operating costs: cost of goods sold (COGS), general and administrative (G&A), and research and development (R&D) — this helps assess margin scalability and operational efficiency.

How the RoCs tell a growth story

From establishing a common language to navigating tradeoffs, RoCs can help you tell a growth story that’s both compelling and defensible by:

Building a shared framework

Measuring and modelling “rule of” components helps you tell a quantified, more defensible growth story. You can accurately frame trade-offs and benchmark realistically against peers and investor expectations with a shared reference point. “This whole exercise is finding common ground — for investors, founders, management teams — on the distribution of possible futures,” says Hinkle. “And the beauty of this Rule of Insight, and capturing these different data points is that it provides a common language for us to debate.”

Engineering durable growth

These aren’t just metrics for fundraising. They’re the building blocks of long-term value creation. “It’s really your growth potential, not just for the next five years, but the growth story you’re going to tell somebody else for the five years after that,” says Hinkle. “That’s what these RoCs are really getting to the heart of.

By focusing on inputs rather than a single output like Rule of 40, you gain control over the levers that drive performance. When you can accurately measure these inputs, you can manage them, making your growth and profitability more predictable, stable, and repeatable.

Helping you see the system, not just the parts

These metrics are interdependent, like threads in a sweater — pull one and the others move. For example, changing CAC might affect GRR; lowering R&D might impact retention. You need to understand not just individual metrics but their interconnected effects.

Ultimately, these RoCs help growth and later-stage companies demonstrate and build enduring value, and when you have a solid grasp on measuring all six of these components it goes a long way to making sure you’re always fundraise-ready.

“These metrics that we’re obsessing over for the purpose of fundraising, they aren’t just a moment in time fundraising need. These are the components of value creation […] because ultimately value is created from durable revenue growth at the highest possible profit margin,” says Hinkle. “If you’re episodically calculating your metrics, you might be on paths that are not exactly as designed or intended. So being fundraising ready at any moment in time generally means your metrics are aligned to what’s most helpful and we can help you get there. A big part of the Onsite effort is to help make sure your systems can produce metrics like these when needed, as needed, and not just every two to seven years when you’re raising capital.”

Lean on me: Partnering with your investors and board

“Investing is a long-term relationship.” says Gosher.

“We’re getting married for the foreseeable future, so there is a two-way relationship.” You choose your investors just as equally as they choose you. Together, you need to believe in the common vision, the common purpose, and you need to want to work together over the next five to 10 years — sometimes in good times, sometimes in bad.

Investors are there to champion, challenge, and partner with your business. Having worked with various founders and companies, they can recognize common patterns, helping you anticipate scaling problems and challenges that arise at certain milestones. And none of that works without trust.

“Most importantly, we need honesty,” says Gosher. “If I don’t know when things aren’t going well, I don’t know how to help you. I don’t know where to dig in. I don’t know what resources to provide you. So honesty is the basis of any good relationship, none more so than in the investor-founder relationship. When you start from a basis of honesty and genuine goodwill, you have a long way to run together.”

As your company grows, so should your thinking about who is on your cap table. Even in later rounds, be intentional about who you bring in. Investors with differentiated sector expertise or networks, and experience with scaling at every stage can offer value. Adding angels with operational experience can be just as important in later rounds as it is at seed.

Each stage of growth brings new needs. Who is the most useful in helping you grow your business today, and who can help at the next stage? What expertise do you need to navigate what’s ahead?

Shaping your board as you grow

Good boards should evolve, too, both in structure and purpose.

In the earliest stages, there’s a lot of uncertainty. The board is there to provide strategic guidance, use their network to help the company grow, and get the right people in place. “So most of the board meeting will be focused on, ‘Am I aiming at the right future? Am I building towards it? And do I have the right people on the bus to actually get me there?’” says Lichtenstein.

At later stages, those three questions are still important, but the board plays more of a pressure-testing role and focuses on governance and helping the leadership zoom out and think about long-term value creation.

“CEOs wake up and they think about the business, they go to bed and they’re thinking about the business,” says Lichtenstein. “Sometimes they’re not looking at every decision through a lens of what is going to ultimately create more equity value for the business […] so a board member later on in a company’s trajectory is really trying to make sure that the execs are getting out of the weeds and thinking about what is actually creating value.”

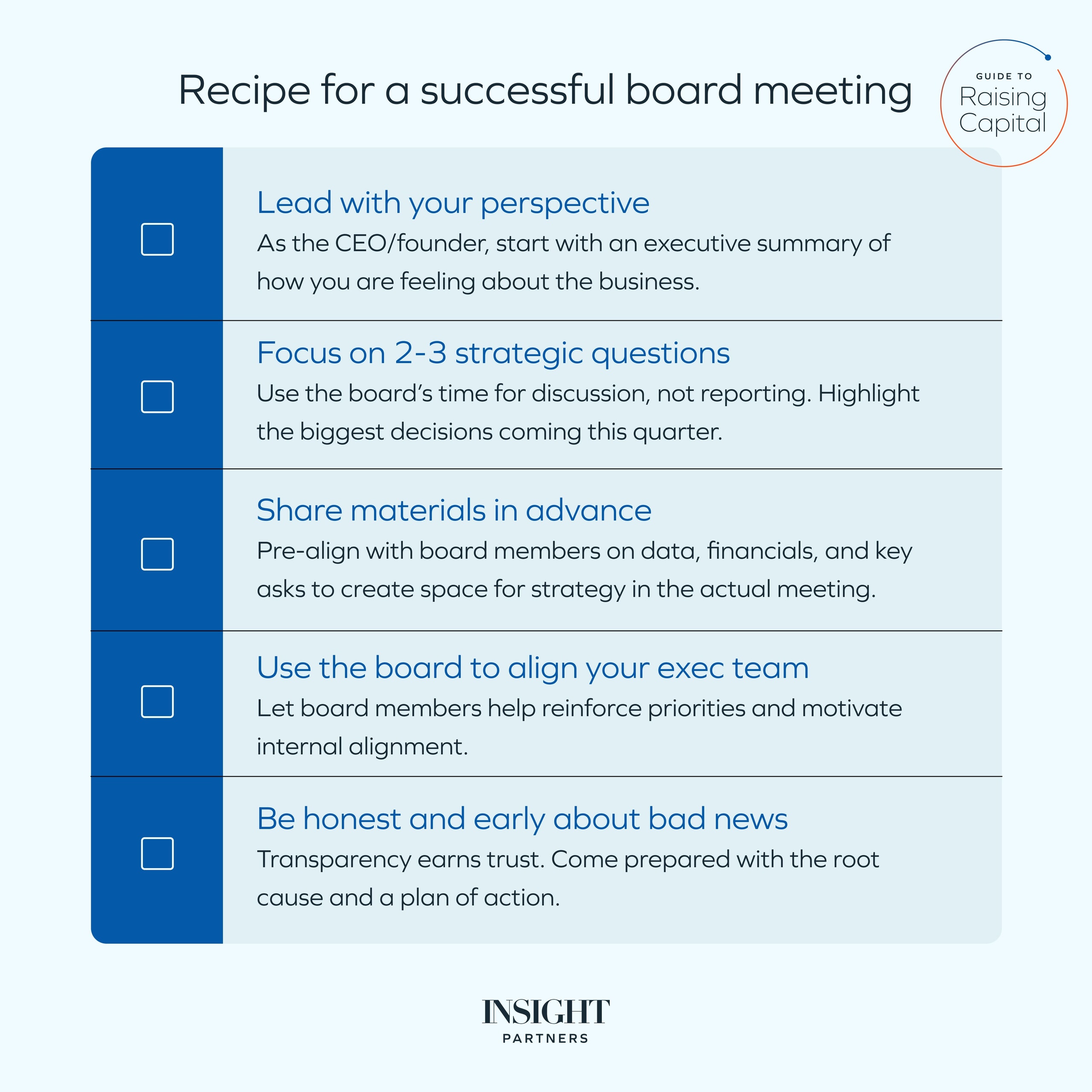

How to partner with your board

Your board is there to have your back and be along for the journey. Your board members want to make sure you and your company succeed. So think of them as strategic assets and partners, not a reporting obligation. “Our most successful founders and our most successful executives utilize the board as true thought partners,” says Lichtenstein. “That meeting should be the most strategic meeting you have all quarter.”

Be transparent and be early with bad news

Your board is there to support you through good times and bad. Communicate bad news to them immediately and directly. Have a hypothesis about why it happened, and a plan for how you’re going to correct it.

Share board meeting materials well in advance to set context and align on goals

Ideally, this means getting all of the day-to-day tactical stuff out of the way ahead of the main meeting. Do a financial call to review all the data and the numbers, and use more regular monthly meetings to cover day-to-day operational issues.

Dive into the two or three big decisions in the coming quarter

You can then use the two– to three-hour meeting to focus on the business’s most strategic priorities and the next big decisions, drawing on the expertise and perspective of your board members about what they think will make the business more valuable.

Align ahead of time

This is critical, especially if you have multiple investors. Particularly for thorny issues, go point by point with each board member and talk to them ahead of time to make sure that on those key topics, you have a sense of where they are leaning today, and what you think they’re going to bring up in the meeting. “In a conversation where there may not be alignment, the best CEOs always make sure that there is a voice advocating for the right position, not too overtly, but nudging the rest of the board in the right direction,” says Lichtenstein. “I think that’s mission critical.”

Use board meetings to align your executive team

You can also use the meeting itself to make sure your executive team is aligned. “Sometimes they just need to hear a certain message from the board members to actually get them to be more motivated or to get them aligned to a certain goal,” says Lichtenstein.

The anatomy of an effective board deck

“The first component of a great board deck is to have the executive summary about how the CEO is feeling about the business,” says Lichtenstein. From there, structure it around the two or three big strategic topics or decisions you want to discuss. Sometimes it’s going to be all about product. Sometimes it’s going to be all about go-to-market. But it should be set up to drive a concrete and actionable conversation with your board.

“The worst board decks are purely report-outs, and they’re report-outs on the most basic metrics,” says Lichtenstein. “It’s a missed opportunity if you have all these folks who can help you problem-solve, and you’re not giving them as much information as you could.”

The metrics you include will shift over time. In earlier stages, it’s about proving potential. “You’re trying to give all the leading indicators that make the board feel comfortable that this is going to grow,” says Lichtenstein. “How many new deals have I brought in? How big do I think they can eventually get? Where am I on the implementation? And then once they’re actually implemented, showing here’s the volume that’s coming through the platform, even if it’s not translating into revenue yet.”

At later stages, it’s much more about concrete results. What did we achieve in revenue? What did we achieve in EBITDA? “At the later stage, you’re thinking about ‘Do I want to IPO? Do I think a strategic wants to buy me? Am I getting close to selling to a sponsor?’ And ultimately, what they’re going to care about is what your financial profile looks like,” says Lichtenstein.

Building back from the future you want

“It’s important for founders to think about the end game, what it is that they’re working to ultimately, because great outcomes don’t happen by accident,” says Gosher.

“Great outcomes happen because of deliberate planning, and being very specific about the milestones that you need to accomplish in order to get to that great outcome.”

The choices you make early in your fundraising journey shape your company’s eventual destination. Whether you’re aiming for an IPO or acquisition, you need to start thinking about it from day one.

Start with the end in mind

At Insight, we call this thinking the DeLorean Playbook: plan back from the future you want.

If you want to raise a Series B in a couple of years, or have aspirations to IPO in the future, what milestones do you need to hit to achieve the goal? Then, you need to put the building blocks in place: the right team, board, and investors to help you get there.

By being deliberate about your end goal, you can plan well ahead. For example, if you want to be bought by a strategic acquirer, you need to be partnering with them 18-36 months before they make that acquisition. You need to be in their customer accounts, proving value to the same set of customers they seek to sell to. They need to start to see that you’re an essential part of their ecosystem, and that they could upsell your product to their customer base.

Good investors facilitate these conversations, using their networks to open doors and build credibility with investment bankers, potential strategic buyers, or additional sources of capital long before the IPO, acquisition, or next raise.

“The founder or the CEO’s major job is to ensure that they sustain or bring about optionality for their business,” says Gosher. “You want to make sure that at any stage of growth you have the options that you need — and only an investor with a wingspan large enough to have those kinds of industry relationships, and that kind of expertise, is really able to help you think through how to sustain that optionality.”

Being clear on your end goal also helps keep everyone aligned. Investors and board members can be very intentional about the kind of advice, service, and partnership they can provide. It creates a clear common purpose, making sure everyone is pulling in the right direction.

Give up equity in fair exchange

“The economics of the whole journey really culminate at the end point,” says Wardi. The end game is when you realize your share of the value that you’ve helped create.

That means picking an investor solely based on the highest valuation each time can be a shortsighted decision. What matters in the end is how much of the company you own at exit or IPO and the valuation of that liquidity event.

When you raise your first round and are diluting by X percent, that is just the start of the journey. Raising capital comes with a cost, as does hiring team members with options and option incentives. It’s common for a Series A investor — and the founder — to be diluted 50% or more by the time the company gets an exit. So you want to make sure that you’re giving up equity in fair exchange: pick team members and investors who can help make the pie bigger — through expertise, networks, and operational support — so you can get a good slice of it at the end.

Through that lens, the valuation of the various rounds along the journey matters less. “It matters much more for the founders to pick investors at the fair valuations, raising the appropriate amount of capital in each round, and finding people and investors who can really make the pie bigger as a whole,” says Wardi. “That’s the rational way to optimize the journey.”

A journey, not a sprint

Fundraising is not just a moment in time, it’s about long-term value creation, and everything you do should serve that purpose.

What matters most is not just how much money you raise, or even when, but why, from whom, and to what end.

Choose investor-founder fit. The right investor brings the right expertise, people, and operational support. You should choose your investors like you choose your key hires — for fit, values, and shared ambition and incentives.

Tell your story with data. Before you’ve built a quantitative track record, show customer usage and iteration towards your ICP. Then use “Rule of” components (RoCs) to measure your inputs so you can better forecast and control your growth.

Lean on your board. Use your investors and board members as thought partners to stress-test your big decisions.

Plan your exit from day one. The best outcomes are built backwards from a clear vision of success.

Ultimately, ask yourself what future you’re building towards, and then go find the capital and the people who can help you get there.