The Future of AI is Augmenting Human Intelligence

Manoj Saxena was for the first GM of IBM Watson from 2006 to 2014, where he led the creation of the world’s first cognitive systems for healthcare, retail, and financial services. He received the IBM Chairman’s award for Watson commercialization and helped form the Watson Business Group in 2014 with a $1B investment from IBM.

Saxena is currently the Executive Chairman of CognitiveScale and the Managing Director of The Entrepreneurs’ Fund. He currently serves as Chairman of the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas/San Antonio.

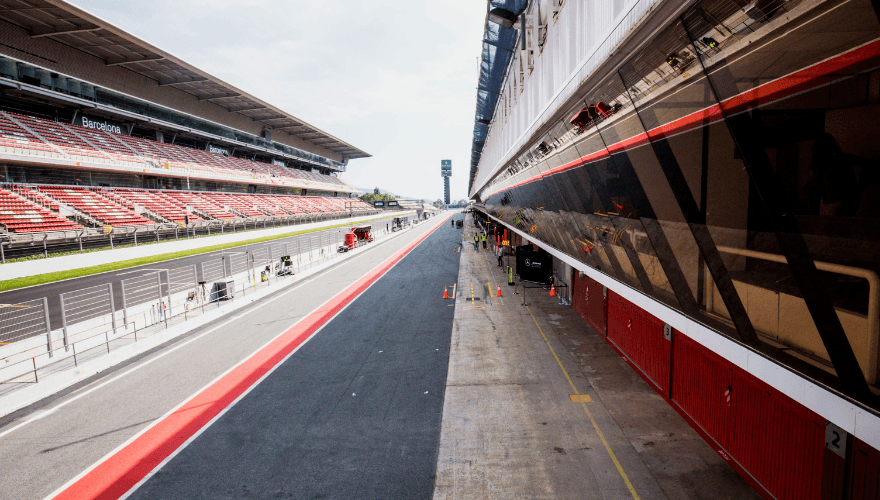

Prior to IBM, he successfully founded, scaled, and sold two venture-backed software companies within a five-year span – Webify and Exterprise. Saxena holds two master's degrees and is an avid auto-racing enthusiast. He has completed track, endurance, and auto rally races around the world including a 24-day Singapore-Malaysia-Thailand-Burma race.

This article is a summary and analysis of Saxena's keynote remarks to the 2017 Insight Ignite Innovation Roundtable event held earlier this year in New York City.

IBM Watson, or Watson, has become the world's best-known artificially intelligent computer (can you name another computer that's been in a television ad with Bob Dylan?).

In 2011, when Manoj Saxena took over as General Manager for Watson, the technology was affectionately referred to as Dr. Watson, connoting a human quality. It was so commonly called this that Saxena's friends and colleagues would frequently ask, "What are you going to do with Dr. Watson?"

One of the first things that Saxena did was stop people from calling Watson, “Doctor”. This was not just semantics. Even then, it was important to Saxena that there be a clear line between human and machine – no matter how smart it was or how smart it could become.

This demarcation has remained a cornerstone of Saxena's outlook on AI, and it illuminates what he sees as the technology's future. As one of the first people on earth to be tasked with managing a thinking, learning computer, when Saxena shares his views on that future, people tend to listen.

They really pay attention when he says that many of the people who work on, invest in, or think about AI have it all wrong.

Amplify, Not Replace.

Most people, Saxena says, think AI computers and learning networks will replace humans, or least take over many of things humans now do. But Saxena posits that AI will not and cannot do this.

He likens the future of AI to the difference between two science fiction computers. One is HAL (the HAL 9000 from the 1968 classic "2001: A Space Odyssey"), which behaved very much like a human and made serious decisions for people – even dramatic, consequential ones. The other is Iron Man’s JARVIS, which stands for Just Another Rather Very Intelligent System. Unlike HAL, JARVIS does not decide anything, but simply makes timely suggestions. According to Saxena, our AI future is JAVIS, not HAL: a world where decisions will continue to rest with humans; AI is an enabler, not an owner of choice.

In Saxena’s view, AI will augment humans, optimizing human performance by making deeply researched, highly connected, timely suggestions and unearthing new information that can make us better, smarter versions of ourselves – an echo of his views related to Dr. Watson. The AI computer isn’t a doctor but a powerful tool that can make doctors better.

Not Hollywood, It’s Still Early

Saxena says Hollywood is way ahead of where today’s technology actually is, even as he references Hollywood and comic book AI computers to make his comparisons. Saxena sees three sub-groups in AI technology and application:

- Artificial Narrow Intelligence (ANI) with a specialty in one area

- Artificial General Intelligence (AGI), which can be as smart as a human across the board

- And Artificial Super Intelligence (ASI), in which computers will be smarter than the best humans in practically every field.

Despite what you may see on the silver screen, AI is at the dawn of the ANI stage – just getting good at adding value in specific specialty fields. Saxena opines that we’re still at least 25 years away from unleashing ASI, which means that we have time to adapt and understand the implications of the technology for societal structures.

Zombies

Because Saxena started a successful career as an entrepreneur, he maintains a strong interest in the intersection of AI and the enterprise. Here, Saxena says, the market is even further ahead of itself than Hollywood is.

"Ninety-nine percent of AI is not enterprise-ready," Saxena said — an assessment that, if even mostly accurate, should merit plenty of attention. "There are hundreds of walking dead in the AI space – doing because they can, not because they should," he said.

“There are hundreds of walking dead in the AI space – doing because they can, not because they should,” he said.

Investors, entrepreneurs, and business leaders are putting their time and money in AI solutions, hiring “math people” to do great things with algorithms, but without much sense of how or even whether there is a viable business application.

To achieve better results, Saxena advises businesses to look at 90-day outcomes from AI solutions and invest in small projects, not overcommit to major, long-term investments. Make sure the technology works and be certain you’re working from outcomes down, not tech down. Rather than create a problem that new technology can solve, the emphasis should be on deploying technology on a sticky challenge.

"People confuse press releases with product," Saxena said. “AI is not about a chatbot; it's about knowledge that the machine has accumulated. It's domain-specific and security-compliant."

In a Black Box

To this point, security and compliance are among the most pressing challenges involved in bringing AI to the enterprise. While AI can add deep and broad information to fields such as medicine and investing, it cannot yet explain why it made a specific recommendation. This hang-up means that many of the most promising AI advancements — the few that could be market-ready — could never pass a legal review.

Imagine, he says, if a patient dies while under a treatment plan created by AI. The AI itself may learn from that experience, but in the event of a lawsuit, we are still unable to put a computer on the witness stand to explain why it suggested one option over another. In this example, when we deploy AI systems in medical settings, the computer still has to reveal and explain every step it takes and defer many of those intermediate conclusions to human review and approval The solutions may be creative, juxtaposing knowledge and computing ideas in a way that humans would take longer to do, but ultimate judgment still lies with qualified professionals.

Right now, Saxena says, as either an AI developer for business or a business interested in deploying AI, if you can’t explain your AI, it probably won’t work. “It’s a black box,” according to Saxena, "and it can’t be in order for it to succeed and be viable.”

It’s Already Alive

Despite not yet having a business or service rationale for much of what AI can do, the basic contours of Artificial Intelligence as a learning, self-correcting digital adviser are already here and in use every day. Systems that scoop up all possible data and create all possible actions, while learning continuously, are boosting customer experiences in diverse markets including coffee, concerts, and cancer, according to Saxena.

Every time Netflix makes a recommendation to a consumer, they’re using a form of AI. In that way, if you think of Netflix as having a physical store with employee salespeople, their AI systems allow every salesperson to be the best possible resource for each individual customer.

That’s both the present and immediate future of business AI, Saxena says. AI will “amplify the knowledge of existing workers,” making every employee your best employee. It would be like giving everyone on your team his or her very own JARVIS business-mission super suit.

Creation of Super-employees

That AI – using learning computers to make super-employees – is happening.

At Dallas Children’s Hospital, a team of nurses and other professionals made up a specialized unit to treat and manage childhood asthma cases. For years, they had treated patients traditionally with set monthly appointments and reviews of medical and treatment records.

Saxena was part of a team that created an AI system for the asthma unit – a system that plugged into and amalgamated existing data sources such as the US Census, public transportation and traffic updates, school schedules, and pollen counts (and developed an automated Twitter feed that shared pollen and other allergen alerts.)

Late one night, while the nurses in the specialty unit were fast asleep, the pollen Twitter feed chirped an alert that an alarmingly high ragweed bloom was expected in a few days in a suburb of Dallas. Under normal circumstances, this data would likely have gone unnoticed.

Instead, the AI system caught the tweet, recognized that ragweed had at least a dozen other clinical and medical names, checked the patient list for those in the impacted area, cross-checked their medical histories and recent treatments, and highlighted a specific subset of Dallas-area children who were likely to be affected by the expected high pollen.

Impressive as that was, any highly skilled nurse could have done the same – had they seen the information in the first place – however, nursing capacity constraints mean that there aren’t sufficient resources to be cross-checking data 24/7, and the computer provided the capacity, doing in minutes what would have taken a human several hours.

The story didn’t end there. The AI system also highlighted a subset of the patients who would not be covered by insurance, if the high pollen caused an asthma reaction. It then suggested possible courses of action, including contacting parents and providing transportation vouchers to come to the hospital for treatment, asking schools to keep specific children indoors, and calling in preventative prescriptions to local pharmacies.

Importantly, the computer provided the options, but the nurses decided which actions to take.

In a test that the system is not always correct, but can learn, when a few of the parents with transportation vouchers actually came in, the AI system learned that was not an especially effective suggestion given cost and time. Next time, it will be less likely to suggest it.

That experience, as Saxena tells it, was like having a 400-year-old nurse on 24-hour duty in the asthma unit. Or, more accurately, turning even the most rookie healthcare provider into a highly aware, highly experienced and resourceful super-nurse.

Core Customer Competency

At the same time, making superhero nurses may not be the real take away from the Dallas Children’s Hospital asthma team experience.

The real outcome – and the important business lesson – is in meeting customer needs. Because of the Dallas Children’s AI system, fewer kids had asthma attacks. Ultimately, the end-user had a better experience. And this, Saxena says, is the core point and the key deliverable that will transform business.

“For a hundred years, the core business competency was supply chain. In the next hundred, customer experience will be the core competency,” he said. That’s the parallel lesson of new economy companies such as Lyft, Amazon, and Netflix – those that can change the customer experience for the better will thrive.

Dark Data Bright Opportunity

Right now, “Most of AI is B2B,” Saxena said. “But B2C is the motherlode.”

This is the future that Saxena envisages. Companies that win, will use “intelligent service [to] transform the customer experience backed by powerful business models.” And, “In twenty years, every business process will be cognitive, AI-powered – just like 20 years ago we started to webify them.”

Still, he cautions that what we don’t yet know is where the real opportunity lies. “Ninety percent of data is dark data,” Saxena said. “Pictures, Instagrams, reviews – computers can’t do anything with that,” he said. So finding more ways for AI computers to access more data –useful data – will unlock the most value for both companies and the customers they need to serve.

That means that industries with vast amounts of untapped dark data – like banking, investing, insurance, and telecom – are best poised to be transformed first, and most deeply, by AI.

Going Vertical

Saxena notes that because we’re only at the start of the Artificial Narrow Intelligence age, investing in vertical AI holds the most promise and is the most necessary. AI computers in business settings don’t need to know everything, Saxena suggested, but they need to know their market space exceptionally well.

The best AI systems will be adapted to their domains. They will know that, for example, the word "coupon" has a very different meaning in retail than it does in investment banking. "Data without context is useless, and context comes from your industry," Saxena said. “Swing” has a different meaning if you’re interested in golf, or in the stock exchange.

"Data without context is useless. Context comes from your industry,” Saxena said.

What Should Businesses Do?

Saxena’s overall advice for businesses considering AI or engaging AI tools is to remember that AI is, “still about driving business innovation, not technology innovation." He also suggested that companies look to utilize AI in three key areas:

- AI-embedded business processes

- AI-powered employee engagement

- And AI-powered customer experience.

Returning to his recurring theme, he reiterated that AI should augment, not replace. "Think of it as “Augmented Intelligence” not “Artificial Intelligence.” It’s man and machine, not man versus machine,” Saxena said.

Man and Machine

Watson, Saxena reminded, was a legacy offspring of the IBM supercomputer, Deep Blue – the computer that shocked the world by beating chess grandmaster Garry Kasparov in 1997 (it was a rematch, Kasparov beat Deep Blue in 1996). Years later, Saxena noticed that since Deep Blue’s chess wizardry in the mid-90s, the average age of a chess grandmaster had fallen by 12 years over a decade.

“New players were using the machine as a coach,” he said. They’d figured out that the true customer value in this great computer was in making humans better players – working with it, not competing against it. This is the harbinger of things to come. We will learn to collaborate with computers to make better decisions, rather than be replaced by them. It’s a future that holds opportunity and promise.