What is Holding Back Scientific Progress and Innovation Today?

The newest threat to innovation in the U.S. are the increasing local technology regulations.

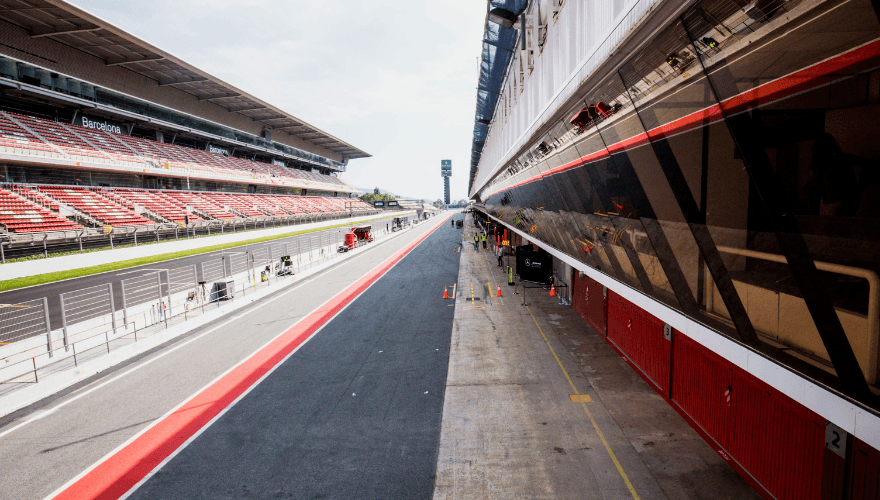

Most of technology has traditionally been regulated at a federal level. One core set of rules allow tech companies to innovate fast and make it so they do not have to spend all their time lobbying states and municipalities.

Alternatively, markets like insurance have traditionally been regulated at the state level and those 50 insurance regulators make innovation very difficult (because firms essentially have to create 50 different products — one for each state). In addition, insurance firms have to spend a large part of their time lobbying legislatures and worrying about upcoming elections that could be a systemic risk to their business.

Even worse, some companies (like cable companies) were regulated at the city level and have to operate in thousands of different jurisdictions (some overlapping) within the U.S. This makes serving customers very difficult (and is one of the reasons cable companies have had historically low customer satisfaction and low Net Promoter Scores).

Until recently, most tech companies did not have to worry about this. Great companies like Microsoft, Intel, Oracle, Salesforce, Facebook, Google, Netflix, and more were regulated at the federal level and could move fast. Yes, they had to think about regulation and be careful about it (the Justice Department had a famous beef with Microsoft in the 1990s) and had to understand it as they entered new national markets (which is the original reason that a company like Softbank exists).

Today, we are seeing a resurgence of local control.

In the last two years, we have seen a core interest in local control, local regulations, and more. This is going to significantly slow efforts of tech companies.

The most obvious examples of where this is true is companies dealing with physical infrastructure like food delivery, Uber / Lyft, Airbnb, scooters, and more. These companies have to deal with things city-by-city and they could have difficulties even moving between city lines. For instance, you can see a scenario where San Francisco and Oakland have such different rules that it makes it impossible for a company like Uber to operate in both (which reduces utility for an Oakland resident working in San Francisco).

The political left has found the 10th Amendment.

Ten years ago, the main proponent of the 10th Amendment to the U.S. Constitutionwere the political right. “States Rights” advocates used to be popular primarily with conservatives who were concerned with federal (and judiciary) overreach. They promoted the idea of states rights and more local control.

But recently, the political left has taken up the States Rights (and even city rights) mantra with gusto. This is partially due to the fact that the left has not been in power for almost two years (this is written in October 2018). This is resulting in many left-leaning cities and states creating their own policies that govern tech companies.

One interesting area is privacy. One would think that privacy should be governed nationally (especially since it is so easy for data to cross state lines). But we have many local entities passing their own privacy initiatives. California recently passed the California Consumer Privacy Act as did the state of Vermont. The city of San Francisco will vote on "Privacy First Policy" in November.

So now we have states and cities passing their own privacy legislation. And these could potentially be in conflict…

For instance, a left-leaning state (like Massachusetts) could pass a “right to be forgotten” legislation (similar to the GDPR statute in the EU) and a right-leaning state (like Texas) could pass a free-speech statute which makes it illegal to take down information that is in the public interest. These two statutes would be in conflict and any tech firm operating in both states (which is pretty much all of them) would have trouble complying. And what do you do with someone traveling from Austin to Boston?

Privacy is just one example.

California recently signed on to the Paris Accords for global warming. So states are starting to have their own foreign policy that could be in conflict with the national foreign policy. Of course, if you are an environmentalist, you may be happy that California is taking a leadership position. But you can also imagine a states-rights argument going the other way (where a state decides have higher emissions than EPA guidelines).

Some cities are even wading into immigration. Immigration has traditionally been one of the core federal government functions. But today many cities call themselves Sanctuary Cities (this includes San Francisco, Los Angeles, Boulder, Hartford, St. Petersburg, Atlanta, New Orleans, Boston, Detroit, New York City, Seattle, and more). These cities are specifically saying they will not comply with federal immigration rules and will not enforce them.

Again, you might like the idea of sanctuary cities because you might believe the U.S. should have more lenient immigration policy. But this does set up a precedent of cities in the future having a MORE restrictive immigration policy than the federal government. Imagine a scenario where your company moves its office to the next town over and finds out it needs to fire two star immigrant engineers because they are not allowed to work in that city. That could be coming.

Local regulations are great for large incumbents.

Massive companies can deal with large regulatory burdens and conflicting rules. They also can pay for lobbyists to change rules to allow their narrow use-cases to operate.

Little innovators can get stifled pretty quickly in a world where every municipality could conceivably have their own rules.

Summation: The newest threat to innovation in the U.S. is the increasingly local technology regulations.