The state of the robotics ecosystem: The tech, use cases, and field deployment

Application-level AI has rapidly transformed how humans interact with computers, from copilots in the enterprise to personal assistants in everyday life. But the next frontier isn’t just digital — it’s a physical world where intelligent robots become a “read/write API to physical reality.” AI agents are redefining productivity. Physical agents will redefine labor.

Progress in robotics’ foundation models — driven by advances in deep learning, richer training data from teleoperation and simulation, and cheaper hardware — is closing the gap between research and deployment. In this environment, vertical Robotics-as-a-Service (vRaaS) offers one possible path to commercialization for the next era of robotics, focused on solving specific, economically valuable tasks.

This perspective is informed by numerous conversations with researchers, startups, industry incumbents, and conversations within Insight Partners. This article covers the current state of the robotics ecosystem, including key technologies, commercial use cases, deployment challenges, and strategic pathways for scaling.

The industry

The history of robotics is a story of reinvention, with every generation shaped by advances in hardware, compute, and intelligence.

Initially, there was tightly constrained automation: hard-coded machines bolted to factory floors, repeating precise movements in controlled environments. These systems were useful only within narrow industrial applications and were largely rules-based — they followed explicit instructions rather than pursuing goals. The Unimate, for example, deployed at General Motors in the 1950s, represented an early commercial use of a robot arm capable of tasks like die-casting and welding.

In the late 2000s, mobile robots were equipped with sensors and simple planning algorithms. The PR2 robot demonstrated what was technically possible, even if it was, in some ways, commercially premature. The hardware could move and “see” but lacked the necessary compute for control and perception systems to operate reliably in unstructured settings.

The PR2 was one of the first robots to natively use the Robot Operating System (ROS), an open-source framework for managing robots. Engineers didn’t have to spend as much of their time re-writing code and building prototype test beds.

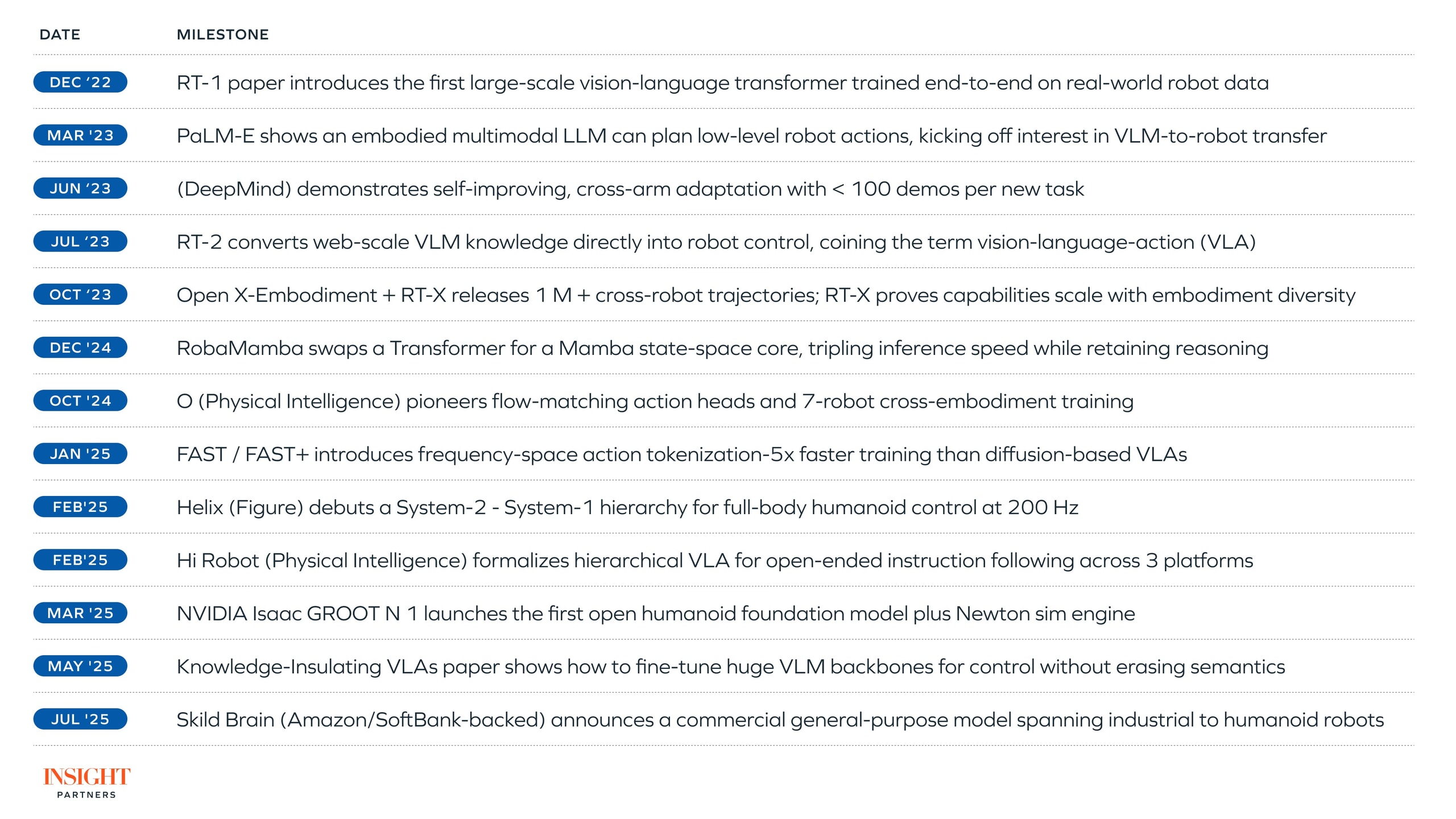

In the past decade, there have been rapid advances in both software and compute. Around 2015, breakthroughs in reinforcement learning, simulation (e.g. MuJoCo), and imitation learning allowed robots to gain motor skills through data rather than hard-coded rules. Data went into the system; robot software came out. Then came Transformers. By adapting similar architectures to those behind frontier large language models (LLMs), like OpenAI’s GPT, researchers trained vision-language models (VLMs) like RT-1, which understood and associated text descriptions with real-world images and videos.

VLMs evolved into vision-language-action (VLA) models like RT-2, which extended those multimodal representations to action space – allowing robots to apply knowledge learned from text, images, and video to physical tasks. Since then, progress has accelerated, with multiple research groups racing to build true adaptive learning models that can execute new tasks without retraining.

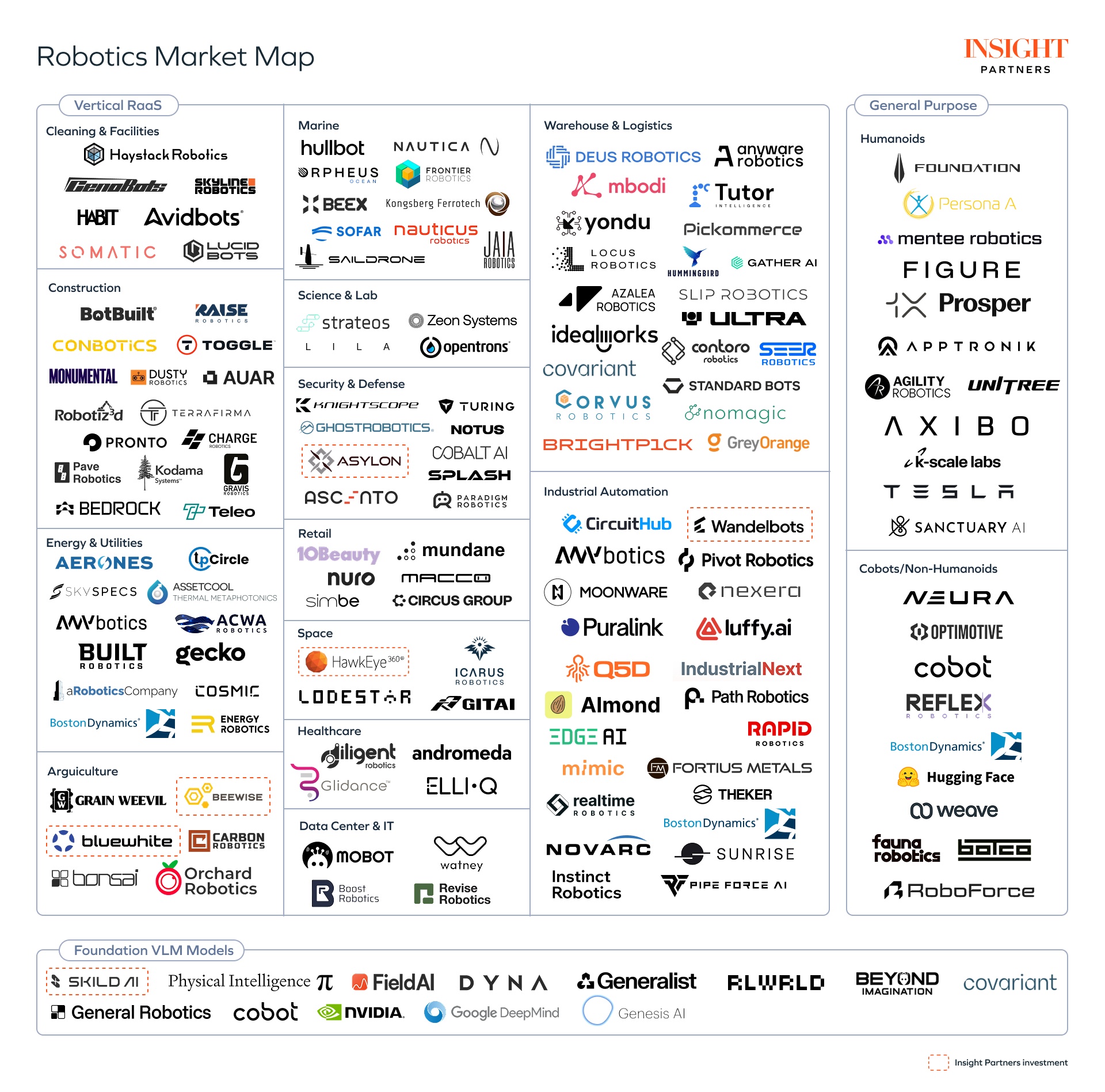

Today, billions of dollars are flowing into humanoid platforms (e.g., Tesla Optimus, Figure, 1X NEO, Agility, Unitree, and others) driven by the belief that humanoids are best suited to navigate a world designed for the human form and that robot manufacturing costs can be reduced by producing a single, versatile robot model at a large scale. At the same time, companies like Skild and Physical Intelligence are developing generalized “robotic brains” – robot AI software systems capable of adapting across a wide range of hardware form factors.

The gap between research breakthrough and commercial viability continues to shrink dramatically, and what once took years is now unfolding in months.

Data, simulation, and the new hardware economics of robotics

Generative AI agents like OpenAI Deep Research can understand goals, break them into steps, and carry them out with context for over 20 minutes without human input. Similarly, as foundation models adapt to the physical world, with robotics researchers building systems that echo the blueprint of LLMs, longer-running systems are a big prize. Making this vision real requires many advances.

One challenge is data scarcity. Scaling laws in LLMs have shown power-law reductions in model loss as dataset size increases, with similar performance gains observed when training with synthetic data. While the LLM community grapples with diminishing returns to pre-training data and is adding new techniques like building post-training reinforcement learning environments and inference-time compute scaling, robotics faces a more fundamental constraint: The complexity of the physical world makes collecting high-quality, pre-training data a bottleneck. As the Skild team observed, “A simple back-of-the-envelope math says that even if the whole population of Earth collects data, it will take years to reach 100 trillion trajectories.”

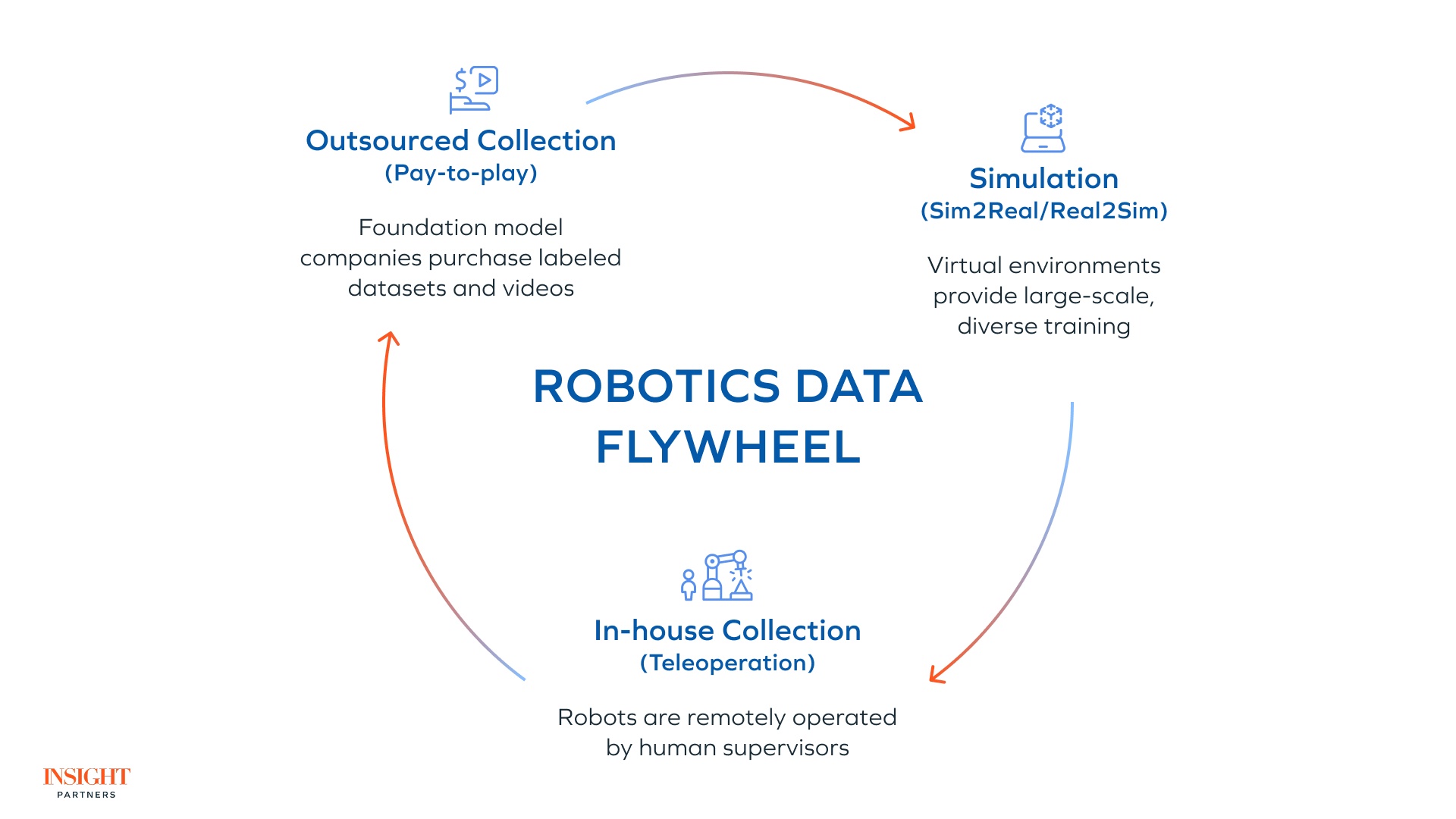

We see a few data acquisition strategies forming today:

- Outsourced collection (pay-to-play): Some foundation model companies collect data through partnerships with industry collaborators. Others purchase labeled datasets from companies like Segments, Kognic, Encord, and Roughneck, which have adapted a “scale AI-like” model for collecting trajectories in robotics.

- Simulation (Sim2Real / Real2Sim): Simulation, in some ways, is the robotics equivalent of synthetic data generation for LLMs. The idea is to effectively use virtual simulations of real-world environments to create large-scale, diverse training experiences for robots. It’s especially valuable for edge cases and tasks that are too dangerous or costly to collect manually in the real world. Techniques like Real2Sim (using real-world data and experiences to improve and refine simulations) and Sim2Real (training robots on simulated environments at a large scale before testing in the real world) complement increasingly world model-like systems like DeepMind’s Genie 3, Meta’s V-JEPA 2, and Tencent’s Yan that allow robots to practice and learn.

- In-house collection (teleoperation): Teleoperation, or using remote human operators to control robots, has allowed for high-quality data collection that captures context around both the action and perception layers, helping to bridge the Sim2Real gap.

Each of these strategies has matured in recent years, reflecting a shift from ad hoc data collection to more structured, scalable pipelines. Teleoperation, though not new, has benefitted from advances like faster networking, improved data pipelines, and more capable hardware. Simulation, once a research luxury, has seen advances in physics fidelity, and Sim2Real transformation that have narrowed the reality gap. Tools like MuJoCo, NVIDIA Isaac Sim, Habitat, and Gazebo allow teams to pre-train, test, and validate robotic policies in-silico without committing to physical trials.

As NVIDIA’s Jim Fan notes, an effective strategy can be the marriage of all three: Where internet-scale data sets are priors, simulation enables infinite testing against actions, and teleoperation bridges some of the Sim2Real gap.

Hardware innovations have also improved the economics of robotic components. Modular design and open-source hardware have created an increase in supply due to increased competition and economies of scale. Advances in sensor and vision technology have made robotic perception more compact and affordable, while commodity motors and actuators have brought similar affordability to the action layer. Not to mention, improvements in tactile sensing, dexterity, and adaptability have expanded the range of tasks that robots can perform.

Platforms like Unitree’s R1 humanoid now ship for $5.9K, and industrial arms that once cost high six figures are available for $50 to $100K. HuggingFace recently unveiled two humanoid robots — HopeJR and Reachy Mini — the latter of which is expected to retail for as low as $250 to $300. Both are built for baseline compatibility with LeRobot, Hugging Face’s open robotic tooling.

Verticalization versus generalization

The question is no longer simply whether robots can perceive, plan, and act in the physical world — it is how these capabilities will be packaged and commercialized. Two strategic paths are emerging between generalized foundation models, which aim to replicate the trajectory of frontier AI labs by scaling models across tasks and form factors, and verticalization, which builds tightly integrated, domain-specific systems that prioritize reliability, safety, and integration into existing enterprise workflows. Understanding this fork is critical because it determines where early commercial traction is most likely to appear and where enduring advantages may accumulate.

As foundation model companies raise hundreds of millions of dollars chasing the vision for a ChatGPT-like generalized foundation model, a few trends are emerging.

Scale is still winning (in line with the bitter lesson)

Just as LLMs moved from task-specific models to large-scale pre-training, robotics is shifting from single-robot datasets like RT-1 to broad, multi-embodiment corpora — powering models like RT-X, GR00T, and π0. These models demonstrate meaningful generalization across form factors and tasks, from folding laundry and bussing dishes to packing groceries and basic tool use. Figure’s Helix shows two humanoids working together to put away groceries, and Physical Intelligence’s π0 performs dozens of manipulation tasks across seven robot types.

There’s convergence on hierarchical architectures

Figure’s Helix, π0.5, and NVIDIA’s GR00T each use a two-part system inspired by Daniel Kahneman’s System 1 / System 2 framework. A high-level “System 2” model plans actions in semantic space (like language), while a low-level “System 1” controller handles real-time motor execution. Since System 2 reasons are language-like, symbolic representations, they are generalized more easily across tasks and platforms.

Researchers are already experimenting with chain-of-thought reasoning for hierarchical planning. In contrast, System 1 is harder to abstract, constrained by physics, safety, and latency. Some researchers believe that true generalization in robotics will require a single holistic system working across both System 1 and System 2.

Speed is still a bottleneck

The push toward faster action generation mirrors a key shift in Natural Language Processing (NLP), when Transformers replaced Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) as a more accurate and faster alternative. In robotics, traditional Transformer-based and diffusion-based models are often too slow for real-time control. Newer research, like flow-matching and token compression (FAST), can allow millisecond-level action generation, with real-world control loops running at 50 to 200 Hz across systems such as π0, 1X, and Figure’s Helix, but these are early-stage techniques.

Model integrity hinges on better fine-tuning and evaluation standards

As robotics foundation models get larger, knowledge insulation (retaining prior knowledge during fine-tuning) has become as important as it was in the early LLM era. At the same time, real-world deployment is surfacing new failure modes, especially under out-of-distribution conditions. But without standardized benchmarks or robust evaluation suites, it’s difficult to measure generalization, regressions, or safety performance. Emerging efforts like RoboArena, which aim to crowdsource real-world evaluations across diverse tasks and settings, represent promising steps forward, though they are not yet widely adopted.

Reinforcement learning is crucial for adaptability and real-world generalization

Reinforcement learning (RL) is becoming critical in robotics, where data quality, cost, and sample efficiency create natural constraints. The most common approach, RLHF (Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback), delivers strong initial results through teleoperation but struggles to scale because it relies on continuous human oversight.

Emerging methods such as MetaRL aim to train policies that quickly adapt across tasks and robot morphologies, while frameworks like ReinboT combine imitation learning with offline RL to emphasize high-quality historical data. Meanwhile, algorithms such as the new FastTD3 accelerate policy training to just a few hours through large-batch parallelization. As these techniques mature, RL remains a critical bridge between research and scalable real-world deployment.

Limited domain diversity and task specificity remain a structural constraint; nuanced industrial workflows demand equally nuanced data. Out-of-domain failures remain common but opaque, and a lack of explainability hinders systematic correction.

Language-oriented foundation models have thrived first in high-value, low-stakes applications where users don’t demand perfect accuracy, but instead, prize fluency, speed, and human-editable drafts. Use cases such as deep research, creative work, writing and editing, coding, summarization, and translation have all swung heavily toward generalist models.

In robotics, foundation action models are making rapid progress in general humanoid tasks. For example, folding laundry, picking up dishes, and taking out trash. Many enterprise use cases, however, are different: They involve complex, mission-critical workflows with many more variables at play, highly controlled environments, rigid tech stacks, and strict integration requirements.

For example, consider a utility-pole inspection robot operating in a hazardous environment: The robot needs to comply with FAA flight regulations and integrate with asset management systems. Or an autonomous system in oil and gas: The robot would have to adhere to OSHA and PHMSA safety standards, connect with inspection management platforms, and feed operational and maintenance data into ERP systems for fleet tracking. Unlike LLMs, where generalist models may get you 80% of the way there, robotics may start closer to 60%, requiring more domain-specific tuning and integration to bridge the gap.

Verticalized robotics-as-a-service (vRaaS) companies targeting specific verticals are starting to build assets that are difficult and expensive to collect. Early enterprise contracts don’t just bring revenue; they also grant exclusive access to hard-to-replicate, proprietary datasets and reinforcement learning environments. For many vRaaS companies, models are only one part of a larger full-stack system that often includes supporting software, integrations, and tight feedback loops.

The anatomy of vertical robotics

As businesses start to automate complex and physically demanding tasks, we’re seeing a few trends emerge.

Simulation and teleoperation refine base-level Vision-Language-Action Model with Speech Instructions (VLAs) on task-specific data. The Mobile ALOHA project, for example, highlights how this can scale: By co-training on existing static datasets with supervised behavior cloning, success rates improved.

In more complex or safety-critical applications, teleoperation isn’t just a training tool — it’s part of the product itself. Companies such as Teleo retain a human-in-the-loop with their “supervised autonomy” model, which inherently boosts site productivity and visibility, while also providing safer conditions for heavy machinery operators. Over time, continuous learning and post-deployment model optimization might support a gradual shift toward full autonomy.

The mechanics of commercialization are equally important. In cases where human-in-the-loop is a feature of the end product, mimicking components from “legacy” machines can ease onboarding and accelerate adoption. Maintenance and system oversight require some level of hand-holding as enterprises acclimate. Providing clear visibility into system status, performance, and output (often through SaaS-style interfaces) can help smooth the transition toward full autonomy.

Historically, “unintelligent” robots have been sold like any other machinery — often beginning as R&D initiatives before transitioning to one-off hardware purchases treated as capital expenditure. This model demands large upfront payments, high integration costs, and long sales cycles. As a result, many robotics companies build services-heavy models to generate recurring revenue over time.

As robots evolve into intelligent systems of actions and enterprises grow more comfortable with deployment, we’re seeing increased adoption of the Robotics-as-a-Service (RaaS) model — leases instead of one-time sales, and usage-based or recurring pricing tied to ROI or task completion rather than time-on-site.

RaaS has some similar investor-friendly traits as SaaS: high gross margins, strong retention, and fundamentally recurring revenue. But there are also important differences: Since the vendor is paying for the robots up front, things like the real depreciation schedule (how fast the hardware erodes in value) and cost of the hardware ingredients both matter a lot to cash flow and real economic viability.

Robotics market map

We are seeing the vRaaS model emerge in environments that are inaccessible or hazardous to humans. For example, mining. Today, solutions from Anybotics, Gecko, and Boston Dynamics serve primarily as data collection vehicles, capturing sensor and visual inputs during routine inspections to improve uptime. Given limited intelligence today, they’re deployed mostly in hard-to-reach areas, with humans managing the rest.

The next generation will go further, automating data capture, audits, and inspections within platforms like SafetyCulture or Field Eagle. Eventually, vRaaS systems want to evolve from simple inspection to doing something useful in the real world. For example, as robots flag issues, they could trigger fleets of “repair robots” capable of performing corrective actions in situ.

Here are a few real-world examples:

1. Cleaning

Cleaning demands comparatively less intelligence and tolerates small errors, with ROI driven more by consistency than perfection. LucidBots uses drones for window cleaning, while Skyline Robotics mounts robotic arms on scaffolding to clean skyscraper facades. In the maritime world, Hullbot deploys underwater robots to clean ship hulls, reducing drag, saving fuel, and cutting emissions.

2. Inspection and maintenance

Inspection sits close to cleaning in intelligence, but maintenance goes further, demanding complex reasoning and intervention. Energy Robotics, Anybotics, and Gecko Robotics deploy ground robots and drones to inspect critical assets across oil rigs, mining sites, and power infrastructure. EdgeAI and Puralink send mobile robots into sewer pipes and manholes for underground inspections. Meanwhile, early systems of action are emerging: Pave Robotics and Robotiz3D aim to automate crack-sealing on roadways, while Boost Robotics and Watney are building systems that diagnose and address issues in data center environments.

3. Manufacturing and industrial automation

Manufacturing was one of the first applications of robotic systems. The shift today is from rigid, pre-programmed motion to adaptive systems that adjust to changes in demand or process. ROI comes from on-demand production, reducing or even eliminating need for inventory. For example, Q5D’s robotic cells automate wire harness design and assembly. IndustrialNext and Sunrise are building autonomous cells where robots dynamically adapt to capacity and process data in real time. Meanwhile, Revise Robotics and Molg’s robotic arms automate electronics refurbishment. All point to the same destination: Factories that run themselves.

4. Warehouse and logistics

Physical inventory management and pallet transport have become competitive, given the highly repetitive and time-consuming nature of the tasks. Accuracy remains a key barrier to adoption, further complicated by fragmented software and difficult integrations. Locus Robotics addresses this with a human-in-the-loop model: Its carts support workers in point-to-point transport and picking. Corvus, on the other hand, takes a fully autonomous approach, using drones for inventory scanning, though its focus remains on identification rather than manipulation. Other solutions like Ultra and Idealworks are building broader task automation platforms designed to scale across multiple warehouse functions.

5. Security

The opportunity in security lies in proactive, comprehensive monitoring and faster response times. Asylon Robotics, focused on protecting critical assets, exemplifies this with its RobotDog and drone services, tightly integrated with AI-driven command software and overseen by a human-in-the-loop RSOC center. Knightscope similarly provides patrolling robots for public and commercial spaces, while Splash focuses on maritime security with autonomous patrol boats.

6. Heavy machinery

Heavy machinery perhaps most closely mirrors the complexity of autonomous vehicles, albeit typically in more controlled environments. In construction for example, companies like Teleo and Bedrock are developing modular teleoperation hardware that retrofits existing machines, improving reliability. In agriculture, where environments are more predictable, companies like BlueWhite are gaining traction with modular hardware for fully autonomous tractors. Beewise, meanwhile, offers a robotic platform to automate beekeeping. As with AVs, modular retrofits lower barriers to adoption while building the data foundation for full autonomy.

Field deployment considerations

In practice, the successful deployment of robotics systems depends on variables ranging from hardware supply chains to serviceability and safety barriers. While nuances vary across industries, we’ve distilled some broadly applicable learnings from buyers here, along with a few open questions we’re asking as we diligence vRaaS companies.

1. Hardware readiness

- Modular systems can be helpful, particularly for use cases that have high integration lift.

- Custom-built hardware stifles scaling unless it unlocks access to data or capabilities that off-the-shelf options cannot.

- Some buyers repeatedly stress that, at least with today’s tech, humanoid or animal-like forms are rarely the right fit if simpler form factors achieve the task more efficiently (of course, this could change if humanoid robots achieve more generalization and massive manufacturing scale that crushes the cost curve).

“Partnering with third-party hardware providers…helps them scale faster, but for us it means we need clear specs on hardware region compatibility and support, especially if we look at maintenance and spare parts.”

— Leader at F100 renewable energy company

“A perceived benefit [to] walk on four legs doesn’t mean it’s stable [compared to a wheeled robot].”

— Robotics lead at global O&G major

Key questions:

- Is the hardware custom-built for each use case or modular/off-the-shelf?

- How much of the performance comes from hardware vs. software?

- Is there a clear path to manufacturing at scale?

- How mature is the form factor and mechanical design, and how well does it suit the use case?

2. Deployment friction

- Even when marketed as easy to install, systems almost always require adaptation to facilities and workflows. Aligning new robots with existing IT/OT systems (ERP, WMS, CMMS, SCADA) often creates hidden complexity.

- Buyers sometimes hesitate to cut over from manual workflows until robots prove sustained accuracy and uptime, which raises the importance of pilot programs.

- Accuracy-critical, unstructured environments expose limitations in stability and perception. Here, automation must progress gradually — from teleop and data collection to autonomy.

- Especially in energy and mining, meeting ISO/CE/EHS requirements is a gating factor. Robots connected to OT are treated as potential entry points for attackers and must pass penetration testing.

“The first thing you have to understand is that any solution will need some changes in your warehouses…you have to adapt your warehouse to the solution you are going to implement.”

— Head of Automation at a F100 logistics company

“Today we are probably…at 85% reliability on the information that’s coming through. We were probably 40% when we first started.”

— Former CDO at a global mining company

Key questions:

- How repeatable is deployment across sites?

- How long from delivery until the robot performs real work?

- What systems does it need to integrate with, and what connectors have already been built?

- How easy is it for customers to switch vendors?

- What regulatory barriers stand in the way of deployment?

3. Serviceability and uptime

- Consistency matters as much as peak accuracy – of course, customers care about sustained uptime, not just one-off high performance.

- Service contracts and preventative checks are expected to be lightweight and predictable; otherwise, ROI breaks down. Over-engineered systems can create hidden support burdens that undermine adoption.

“You [shouldn’t need] a hardware engineer, an electrical engineer, and a software engineer [for maintenance]…You send three people on a chartered helicopter every time there is a failure.”

— Robotics lead at a global oil & gas company

“Robots might be 95% precise today, but if they are 95% every single day, that’s powerful.”

— Leader at a F100 renewable energy company

Key questions:

- What failure modes happen most often, and how fast are they resolved?

- What is the uptime SLA, and how is it actually measured in practice?

- How much support infrastructure is required (spares, technicians, monitoring)?

- Where is the budget being driven from? How does the end buyer view purchasing decisions?

- What line item in the P&L does this impact (labor, uptime, safety)?

- What’s the ROI/payback under conservative assumptions?

If you’re building or deploying in this space — or have a perspective on the future trajectory of the field — we’d welcome a conversation.

*Note: Insight has invested in Beewise, Bluewhite, Asylon Robotics, Hawkeye, Wandelbots, and Skild AI.