Tech valuations are at a 10-year low — but optimism should be at a 5-year high. Here’s why.

This article originally appeared on Fortune.com.

We have all been through a lot in the past four years. In early 2020, the NASDAQ was at or near record for most of January and February. Things felt great. Then COVID-19 broke out. The rapid adaption of tech, fueled by remote work, led to a massive tech boom and supercharged adoption, innovation, employment, and valuations from the second half of 2020 through Q1 of 2022. Then came war in Europe, rampant inflation, high interest rates, uncertainty, a Great Reset in tech valuations, a banking crisis in the heart of Silicon Valley, and many very hard conversations for CEOs, their management teams, and their boards.

We are now in early 2024 asking ourselves what to expect for the tech ecosystem next. I am hoping we come to look at this year as the first “normal” year since 2019. While there are geopolitical risks that can always disrupt this hope, we should have finally squeezed all of the pandemic-related distortion out of the system — and we have a chance to see some improving demand signals after six quarters of tech budget austerity. For that reason, 2024 is my year of Great (Reset) Expectations.

2024 is my year of Great (Reset) Expectations

The mindset shift from the 2021 boom to the Great (Reset) Expectations of 2024 is significant — and healthy for the ecosystem. But there are significant implications for founders and investors. At the highest level, the biggest shift can be expressed succinctly: The cost of failure has increased dramatically. This is the result of three major differences from late 2021 to today, including diminishing returns regardless of demand, valuations remaining closer to 10-year lows than the highs of 2021, and capital being more expensive — and that’s assuming it’s available.

Demand can and will experience diminishing returns — eventually

There are so many attributes of software that defy classical economic ideals. Most businesses get the benefit of neither high gross profit margins nor high recurring revenue. Software — particularly SaaS software — gets both. Those are the ingredients for high growth and high margins, which can lead to “the rule of 50 or better,” whereby returns are the sum of growth rate plus profit margin.

In the boom, tech companies experienced a remarkable level of demand responsiveness to sales efforts. Unlike the traditional concept of price elasticity, this phenomenon was characterized by the market’s reaction to the expansion of the sales force and sales activities, rather than to changes in pricing. Scaling up sales operations or marketing efforts led to a proportional increase in sales results.

It was like a finance cheat code. To maintain a stable customer acquisition cost (CAC), improvements in efficiency must offset the diminishing returns of market penetration. This is reasonable if you are increasing sales spend by 20%. But 200%? That’s so much harder. Going from 200 sales reps to 600 sales reps is a wildly different management model with much more acute needs for advanced systems and leadership. But during the boom, the sales stats all looked great as companies tripled sales spend. How could this be? Part of the reason was that companies were increasing software spend in anticipation of their own hiring plans, but demand was exaggerated unbeknownst to the industry because there was a widespread miscalculation on how fast teams would be scaling their tech effort. That music stopped in Q2 2022, and we saw CAC deteriorate instantaneously.

Obsessing over efficiency — or at least the path to efficiency — will always be fashionable, and the Great Reset reminded us of that.

The solution was to fix spending to align with acceptable CAC metrics. By and large, that has happened, and public SaaS stocks are, for the first time in many quarters, starting to see an increase in net new average recurring revenue. As we model moving forward, we should take care not to assume the same sales responsiveness as we saw in the boom cycle. If you plan to scale quickly, ensure measurable outcomes at short intervals. Adding too fast may lead to job cuts, and wisdom dictates it’s best not to overextend initially.

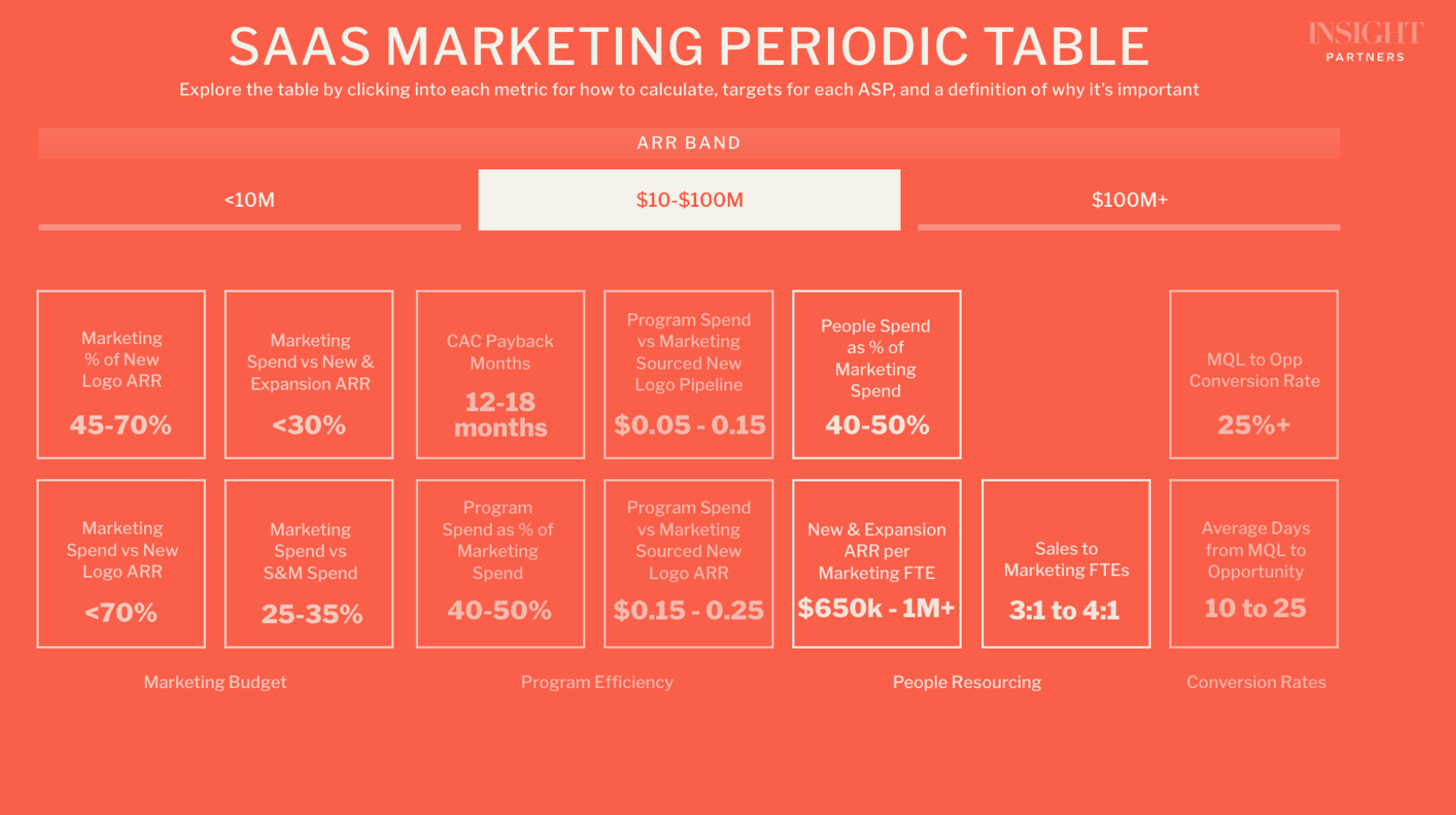

Obsessing over efficiency — or at least the path to efficiency — will always be fashionable, and the Great Reset reminded us of that. Perfecting your sales efficiency is a great tool for maximizing value. All else equal, the company with more efficient sales and marketing is worth more than the company with less efficient operations.

My Great (Reset) Expectation for 2024 is we will likely see more experimentation in increasing spend while maintaining an obsessively careful measurement of efficiency. Whereas in the boom, you might have “waited out” the path to efficiency by “growing into it,” if you fail to hit your target metrics, it is far more likely that you will be unwinding some costs.

Valuations remain closer to 10-year lows than the highs of 2021

When demand changed as it did in early 2022, there were two painful implications. CAC getting worse means less profit, and slower sales success means less growth. That led to a material change in growth and expectations, which necessarily compresses valuations. Valuation is supposed to be the discounted present value of all future cash flows — less growth and less profit compound to pull valuation down, and this is the reason we saw peak-to-trough valuations fall by up to 70% in the early moments of the Great Reset.

But the cost of failure will remain high as valuations are unlikely to rebound so far that it brings back the “well, I’ll just sell it if it doesn’t work” lever for founders.

One implication of lower valuation multiples is that founders and investors no longer have the “Well, I’ll just sell if it doesn’t work” lever to pull. In the near future, valuations will likely drift upward slightly as net new growth gathers momentum. But the cost of failure will remain high as valuations are unlikely to rebound so far that it brings back the “well, I’ll just sell it if it doesn’t work” lever for founders.

Capital is more expensive — and that’s assuming it’s available

Capital is a fickle thing. There is either way too much, or there is way too little. Interest rates are low, or interest rates are high. The swing up is a glorious thing. It’s what created this boom. It’s what will create the next boom. The swing down is painful. We are still feeling it.

Funds are seeing elongated capital-raising cycles. Valuations are reset lower, and there is less capital flowing into the ecosystem.

With the Great Reset of valuations, there was a massive reduction in exit activity. That means the Limited Partners that back new funds have been slower to make new commitments, as today’s liquidity is tomorrow’s commitment. Funds are seeing elongated capital-raising cycles. Valuations are reset lower and there is less capital flowing into the ecosystem. In boom times, if you try and fail, who cares? Just raise more. Try and fail now? Eeek.

The Great Reset applies to capital availability, and the “unfundable” bar has been raised much higher. However, in 2024, we will likely see more capital activity. But the cost of failure to keep a sufficient cash cushion could still be catastrophic dilution or worse. My general rule of thumb is to tell founders to assume they raise at 409A — the fair market value of common stock. If raising at 409A is accretive, then by all means, let’s do better. If raising at 409A is deemed too dilutive, the best course of action is to curtail burn.

Looking ahead, I am excited for the year to come. 2022 was a Great Reset of valuation multiples. 2023 was a Great Reset of performance expectations. Let’s make 2024 the year we exceed our Great (Reset) Expectations!